If you want to understand the very soul of a Georgian Qvevri wine, Ramaz Nicoladze is the man to ask. We meet him on a sunny day at the end of August in the Nakhshirghele region in the north western part of the Imereti province. We find the winemaker standing on the little dirt track that leads to his vineyard. His blue t-shirt with the slogan “Agriculture now!” makes him visible even from afar.

Georgia happens to be a rather hip place these days, not least due to the natural wines that are fermented and even aged in its Qvevri clay pots. We paid a visit to a small but fabulous vineyard.

Good conditions for Qvevri wines

The rallying cry for these wines, albeit less of a battle cry and more of an unhurried, peaceful movement, hasn’t come from nowhere. Ramaz Nicoladze plays a key role on the biodynamic wine scene in Georgia. He has regular chats with Carlo Petrini, the hero of the slow food movement from Piedmont. It is still a rather small avant-garde group of winegrowers who have chosen to dedicate themselves to the high-quality production of natural wines. But along with the rising interest from abroad comes greater demand. And it’s certainly not come out of the blue. For their work to be a success, Georgians like Ramaz Nicoladze seem to need a specific set of conditions in which to thrive: an exciting history, limited availability, biodynamic production conditions and unique flavour.

Tiny operation, big impact

We follow him through the knee-high grass down a hill. His vineyard is a manageable one, just 1.5 hectares in total, and the cultivation area we’re currently standing on is hardly more than a large wild garden. It is hard to imagine that the wines produced here can be found not only in Europe, but also as far afield as Japan, New Zealand and the USA. The 42-year-old produces 6000 bottles a year, all hand-pressed and fermented in Qvevris. Qvevris are huge clay amphorae that are buried in the soil to ensure cool temperatures during the fermentation process. This method goes back 8000 years in Georgia, even though it was largely abandoned for a long time when the country was obligated to subscribe to mass production methods by its Soviet neighbour.

Good wine needs gut instinct

Ramaz picks a grape from the vine to test the sweetness. He can do this with the help of the Oechsle scale, but he prefers to trust his senses. A good wine has a lot to do with gut instinct. And also with the ideal climatic conditions: ‘We have cool and humid nights in Imereti and high temperatures during the day’, he explains. The soil is clay-based and contains moisture in sufficient amounts that the vines don’t need to be watered. To protect them from intense sunlight during the day, Ramaz lets the grass grow high between the vines. He never uses herbicides or chemical additives, merely a little copper spray for the younger vines to protect the leaves against mould.

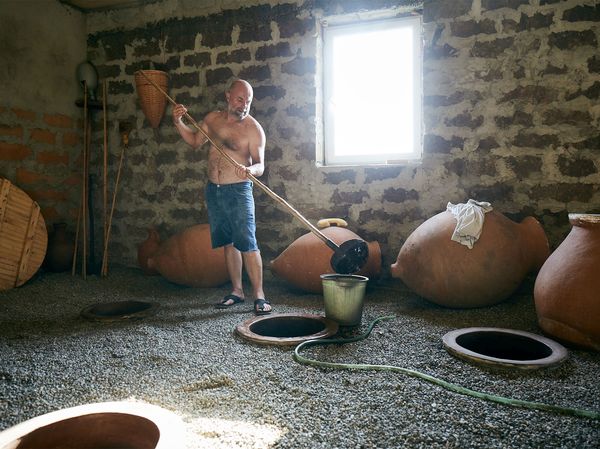

Qvevris are buried in the wine cellar

A little while later Ramaz squats beside the opening of one of his nine Qvevris. They are buried deep in the soil of his wine cellar with only the edge protruding. He slides smoothly down until only his head and headlamp are visible. Using water and a soft brush, Ramaz scrubs the inner walls of his wine amphorae. The last steps he needs to take before the big day. In just one week, the grape harvest will begin.

A great deal of care and passion

‘In Imireti we have our own method of wine fermentation’, explains the winemaker. ‘Unlike the “Full Skin Contact” method, where grapes are fermented root and branch and stored for months, we separate the juice from the skins, seeds and stems for our wines. Five to 20 per cent are then added again during fermentation. ‘It’s an exhausting process’, says the busy winegrower. ‘Freshly prepared mash is like a newborn baby you have to take care of intensively’. Even at night. If the mash is not constantly moved, it will flood out and might become contaminated.

Ramaz pushes some sand aside. A glass plate appears with a tiny hole through which he can tap the wine that has matured in the Qvevri.

Georgian tables are always full

To wrap things up, you just need to decide how to bring together all the components you’ve prepared. You can either combine them with each other straight away or store them separately. As a general rule, you should always let the ingredients cool before storing them in air-tight containers in your fridge. Our 5-day graphic reveals how you can prepare a total of 15 meals from chicken fillets, chickpeas, roasted vegetables, granola, cooked brown rice and sauces.

From yogurt topped with granola through to sweet potatoes for breakfast, from chicken curry through to roasted vegetable salad, see this overview as inspiration that you can change or expand to suit your taste. Of course, you can always pep the dishes up a little with fresh ingredients, such as tomatoes, cucumber, fresh herbs, chopped nuts, a dollop of (plant) yogurt or cheese.

Every wine has a history

And as we empty bottle after bottle, we learn about the emotional stories behind every wine label. Solikouri, a philologist and Germanist, was Ramaz’s friend and mentor, teaching him all about the “Full Skin Contact” method. He has since passed away from cancer, but the wine still bears his name in his honour. Another type of wine, Amivan, is named after his father-in-law, who gave Ramaz a few serious words of advice at the start of his marriage. Ramaz presses the wine “I am Didimi from Dimi and this is my Krakhuna”, which has made it as far as Paris and New York, for an almost blind winemaker. Personal contacts count for so much more than mere money.

A country full of cordiality and hospitality

Here, genuine modesty is combined with an exuberant sense of cordiality and hospitality. Georgians aren’t interested in big performances. They also don’t need an excuse to enjoy a huge feast – here, constantly eating and drinking in good company is a way of life. A meal can easily last up to five hours, and every few minutes someone gets up and makes a toast: to friendship, to family, to children and fertility – and to us guests, our country, our history and our music. Given we can hear Rammstein, a German rock band, rocking away in the background, our Georgian friends certainly seem to appreciate our music. And it’s a mix that seems to suit this country, which is full of quirks and definitely not quickly or easily forgotten. A country where surprisingly good wines are produced in the smallest family businesses, where every stranger is welcome and a guest perceived as a gift from God.