The path to the mountains of the Caucasus is steep and stony. It takes us past Chiatura, a hilly town in the north-western province of Imereti that used to be one of the most important mining centres for manganese ore at the start of the last century. Mountain railways that belong in a museum and disused farmsteads bear witness to its decline. This is a journey back in time. And to the future too.

The 8000-year-old Qvevri culture is suddenly back in the spotlight. The biodynamic winemaking scene has taken an interest in these large clay amphorae, which are still made by hand today as they have always been.

Georgian Qvevri are a focal point of the wine scene

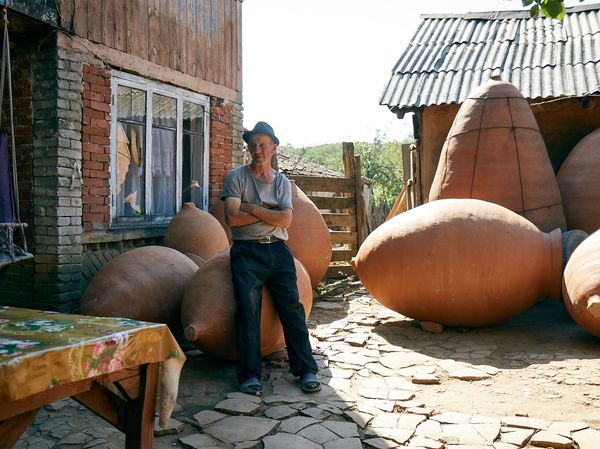

Up here in a small mountain village, which is accessible only via gravel roads that are barely passable thanks to large potholes, is a very special artisan maker. It is a business that is attracting more and more winegrowers from across the world: in Gogi Chinchaladze’s workshop, beautiful huge clay amphorae are created for natural wines. These are called “Qvevris” in Georgian. They are fired from clay and take the shape of oversized lemons. Once completed, Qvevris are embedded in the soil where the cool temperatures provide the optimum climate for the fermentation process.

8000-year-old craftsmanship

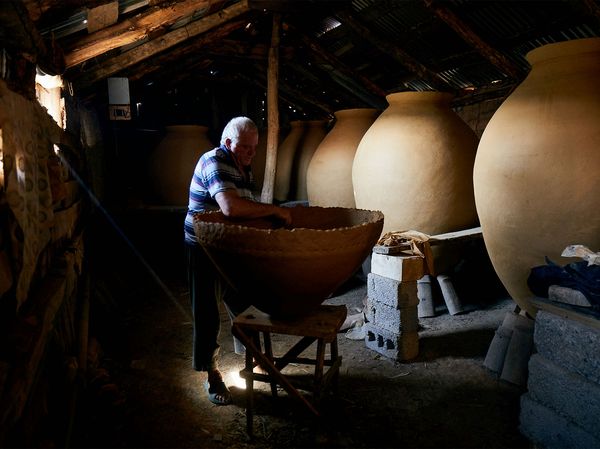

Behind a rickety wooden gate, we discover a paradise. The buildings look like a film set from another century. The large workshop is a wooden crate through whose cracks sunlight penetrates and finished amphorae are standing or lying everywhere waiting to be transported. Gogi Chinchaladze’s order books are full: if you want to have one of the coveted Qvevris, you’ll have a three-month wait to get one. The art of making them is passed down from generation to generation. In the Qvevris, grapes ferment with skin, seed and stems and ripen there without additives over a period of three months or longer. The wine produced is considered archetypal, full-bodied and expressive.

The climate determines the timing and season

Gogi Chinchaladze bends over a half-finished Qvevri and presses clay on the edge with his practised fingers. ‘A vessel is built like a house’, he explains. ‘I can only apply a hand’s width of fresh clay, which then has to be left to dry out’. This is important so that the stability of the material does not suffer. Coil by coil and without measuring to the exact centimetre, a huge vessel is created that has a capacity of between 1000 to 2000 litres. The climate determines how many days it takes Gogi: if it’s damp, it takes longer than in dry weather. This is one of the reasons why production can only take place between May and October: in the winter months it is too damp to work with the natural material.

Even the youngest get involved

Georgian clay is one of the finest pored in the world. Gogi collects it from the surrounding area in a truck. It is mixed with sand and water and processed into a homogeneous mass which must not be too dry or too wet.

The finished vessels are pushed into a gigantic chimney that is bricked up with stones where up to six Qvevris can be fired simultaneously. The firing process starts at a low heat. Two employees shovel wood in gradually until the oven reaches a temperature of 500 degrees. The art lies in producing vessels that are as stable as possible but also thin-walled. Immediately after firing, the inner wall is sealed with beeswax to close the pores.

A magical place where wealth has its own currency

Gogi Chinchaladze makes around 100 vessels during the six-month production period. For a 1000 litre Qvevri he gets 1000 lari, for a 2000 litre vessel he gets double that. If he were to modernise his archaic production process, he could easily earn multiples of this amount. But like so many Georgians, he’s not interested in money. Producing Qvevris is community work, and during the hot season, the men cannot take a day off. It bonds them together. We feel this sense of companionship when we’re invited to sit down at a long table and eat and drink alongside them. Delicious fresh food from the garden and a wine glass that’s always full are testament to the fact that feeling rich has nothing to do with money. This is the Georgian way of life.