THERE IS A FEW PHILOSOPHIES WHICH EMBODY THIS SAYING MORE THAN THE CONCEPT “NATURAL FARMING”, DEVELOPED MORE THAN FOUR DECADES AGO BY MASANOBU FUKUOKA. TODAY, THE JAPANESE THINKER’S THEORIES ARE MORE RELEVANT – AND MORE POPULAR THAN EVER BEFORE.

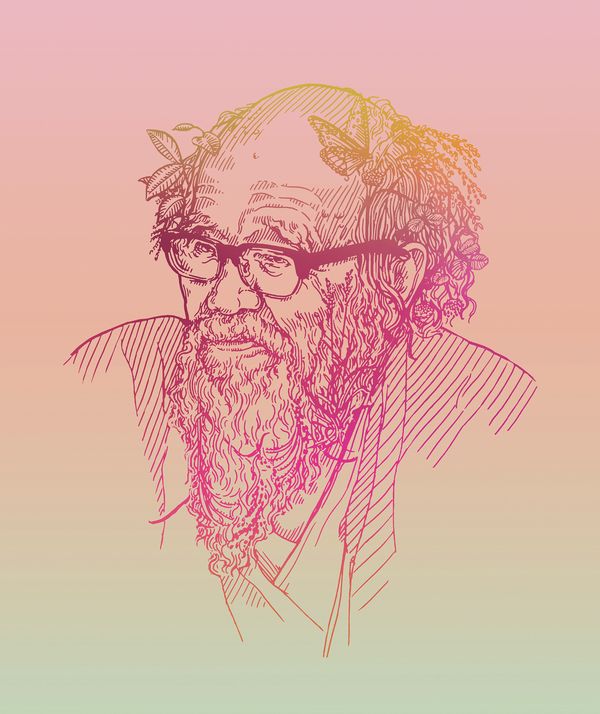

With his bushy white beard,

black horn-rimmed glasses, white linen tunic and a multitude of laughter lines, Masanobu Fukuoka looked a little like a textbook wizard. And, in the interest of accuracy, the Japanese farmer and microbiologist who wrote The One Straw Revolution was actually something of a magician, creating a concept of “Natural Farming” that fascinated scientists and agricultural experts worldwide during his (almost 100-year-long) life and has continued to draw attention since his death in 2008.

Nature is capable of conserving itself

His theory is astonishing in its almost banal simplicity: “Nature is capable of conserving itself.” Fukuoka argues that, as a closed system, it does not require human activity of any kind. What follows from this is that, by leaving nature to its own devices and maintaining ecological balance, farming would actually require less work and less investment; and while our systems are based on the assumption that more productivity is equal to higher yields, an assumption which has long since turned farms into high-performing commercial enterprises, Fukuoka’s natural farming philosophy totally inverts free market economics.

The blueprint is nature

By adapting laws of nature – e.g. specifically combining two utterly different species of plant – Fukuoka managed to double up crop sequencing in one place without needing to plough the earth. In other words, he did precisely the opposite of what has become the norm since the agricultural revolution, replacing monoculture with biodiversity and eschewing chemical fertilisers in favour of natural manures made of protein-rich animal bones, eggshells, fish guts, windfall fruits, apple vinegar, organic house waste and excrement (both animal and human).

With fertilisers, plants lose the ability to grow by themselves

According to Fukuoka, fertilising land is actually counterproductive for the nutrient cycles of plants: seeds which germinate in a natural environment can profit from a rich offering of nutrients in the soil, but as soon as they need human help to grow, they lose the ability to survive on their own and become more susceptible to infection; as they grow more and more used to artificial fertilisers, they actually start to prefer them to natural sources of protein.

Plants are like people

In Fukuoka’s analysis, plants are just like people inasmuch as they need just the right feed at just the right stage in their development; if they don’t get it, they fall victim to pests and stop developing in a strong and healthy way. In his system, there is no need for the pesticides, insecticides, fungicides and herbicides required in conventional agriculture either, because microorganisms such as photosynthesising bacteria, yeast fungi and lactic bacteria will do the work instead.

The natural enemy of weed

Weeds, too, can be tackled with a simple trick: by letting white clover grow all over his plot, other species were crowded out and the soil was enriched with nitrogen in the process. His way of practising agriculture was all about this kind of multifunctional approach, aiming to prevent soil erosion, flooding and sinking groundwater all at once while combating the declining proportion of oxygen in the air, too.

“The ultimate goal of farming is the cultivation and perfection of human beings.” Fukuoka saw agriculture as more than just a way of producing food, but as an aesthetic, even spiritual way of being. For him, farming was a holistic approach to life, and his goal, the “cultivation and perfection of human beings“, would benefit nature, too. Another tenet of his thinking was that natural farming would help growers to emancipate themselves from the agribusiness conglomerates; replacing a hightech approach which required ever more expensive machinery and substitutes, leading to continuous increases in the consumption of resources, natural farming observes and obeys the laws of nature, using the plentiful gifts and useful tools which are already on offer – for free: sun, air, water, soil, warmth, microorganisms and enzymes.

Nobody could dream up nature

Each form of life is part of a highly complex cycle of nutrients in which refuse is recycled and transformed into new resources: nature is, in other words, a set of sophisticated systems which no human would ever be able to dream up.

Natural farming takes over

Today, almost 40 years after The One Straw Revolution was published, natural farming is not just practised in Japan, but worldwide in places such as Korea, Malaysia, Singapore, Vietnam, Thailand, Mongolia and the Philippines; the principles are applicable in every part of the world.

Nature helps itself

Greenpeace’s sustainable agriculture expert Christiane Huxdorff calls Fukuoka “one of the five people who have had the greatest effect on organic farming.” His idea that nature is well capable of conserving itself is something she singles out as being of particular importance: “His philosophy reduces human interference to an absolute minimum, which stands in contrast to conventional agriculture: even the green leaves of potato plants are sprayed before harvesting to make things easier.”

Do-nothing farming

In Huxdorff’s view, farming should be organised holistically, “and that includes halving the production and consumption of meat by 50% by 2050 and stopping the use of chemical and synthetic pesticides. Moreover, food waste will have to be cut drastically.” In principle, all humans really need to do is to sow and reap, so it’s not surprising that, aside from “Natural farming” “the Fukuoka method” also became known as ‘do-nothing farming’. And that is indeed the point: doing nothing (superfluous) will lead to a fine harvest.